1763: The Establishment of St. Louis and African Arrival

Big Idea

St. Louis’ European population remained influenced by Western notions of race and viewed Africans as inferior to English, French, and Spanish colonists. At the same time, free Black men and women lived and thrived in St. Louis in the late eighteenth century.

What’s important to know?

Early Development: Europeans from different country first settled in the Missouri area, including free as well as enslaved Black people.

Black Success in St. Louis: Free Black people in St. Louis in the early years were able to find success, own land, and establish themselves as “aristocracy” in the growing city.

1: Early Development

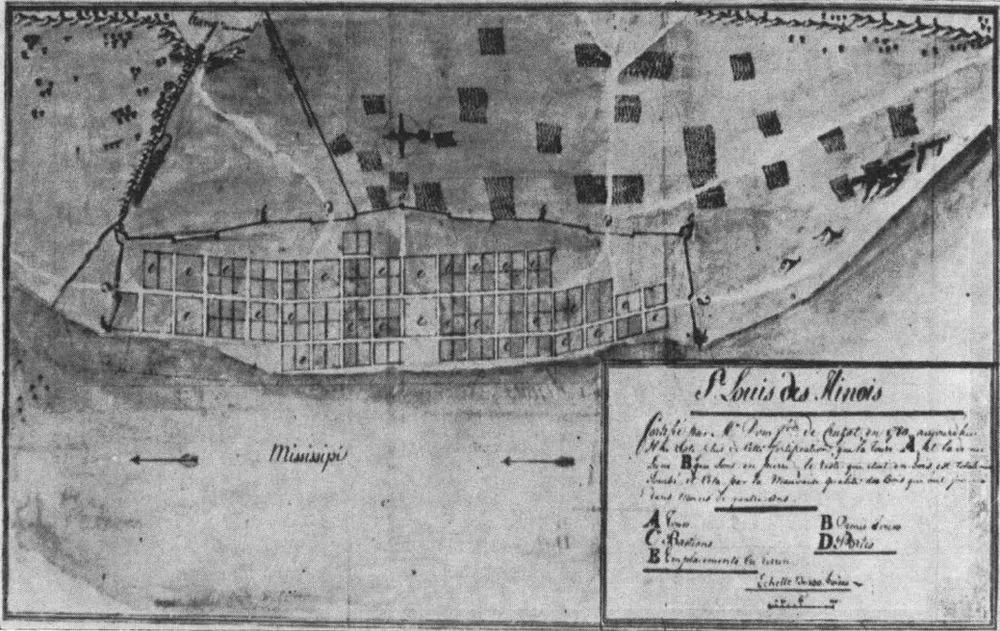

Map of Early Saint Louis

Image Source: The Founding of St. Louis (stlhistories.com)

Cultural diversity in colonial St. Louis meant that French, Spanish, and English were all spoken. Likewise while some Africans came as slaves, a number of Black people living in the region were free (and some even landowners) and counted in the 1722 census as such (Smith, p. 16). Historian Dale Edywna Smith has noted that in early years, “[r]ace and status were not automatically joined from the beginning of the Louisiana colony” (Smith, p. 16).

Laclede Landing at the Present Site of St. Louis, Oscar Edward Berninghaus.

Image Source: The Founding of St. Louis (stlhistories.com)

St. Louis was originally developed under the leadership of a French trading firm. In 1763, the French officially gave the firm Maxent, Laclède, and Company rights to trade in the Louisiana region. Seeking a money-making venture, the St. Louis area became a designated hub for future trade given its optimal location with the meeting of the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers.

However, what was not known by Maxent and Company is that secretly during this time the French had given the Louisiana territory to Spain as part of the settlement of the commonly known “French and Indian War” (Smith, p. 20). News of this transfer of power didn’t reach St. Louis until two years later in 1765 when the town was already under development. Despite the transfer in ownership, St. Louis remained a distinctly French city (Smith, p. 20).

2: Black Success in St. Louis

In the early years of the city’s development, some free Black men and women owned property and ran successful businesses. A 1796 census listed 42 free Black men and women living in St. Louis. (Fausz, 2011).

Jacques Phillippe Clamorgan

Note of Jacques Clamorgan agreeing to pay skins worth $153 to Pierre Chouteau on July 19, 1807.

Image Source: Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis, Clamorgan Family Papers, A0288-00017

Clamorgan arrived in the St. Louis area in 1784 and worked as a fur trader. Originally from the West Indies, he was considered Black but was a free man.

Quite successful, he acquired more than a million acres of land during his lifetime. While he never married, he fathered four children who under the laws of the land at the time were recognized as his children.

One of his grandchildren wrote a book about the success of the family in St. Louis titled, The Colored Aristocracy of St. Louis. (White Sr., 2002).

Jeanette Forchet

Jeanette Forchet was born into enslavement at a French outpost in Illinois. She was freed by the priest who owned her and moved along with other recently freed Black men and women to nearby St. Louis. The city’s founder, Pierre Laclede, gave Forchet a plot of land in St. Louis in 1765 where she subsequently built a house. She married another free Black man and together they had four children — two sons and two daughters.

Inventory and appraisal of personal property of Jeanette Forchet, May 30, 1790.

Image Source: Wikipedia

They raised crops, livestock, and Forchet also had a home laundry business. After her first husband’s passing, she remarried another free Black man, Pierre Ignac. He was a gunsmith and trapper. He died in 1790 and she passed away in 1803. Her grand-daughter, Julie, married a wealthy Black man in 1850 and their family became one of St. Louis’ prominent Black families in the nineteenth century.

Forchet’s life—while rare among the experience of Black people in America—represented the tenacity and success that could be achieved when given the opportunity (Corbett, 1999).

Despite the success of free Blacks such as Forchet, as a French city, Africans — whether enslaved or free — were governed under the harsh rules of the Code Noir. For example, Forchet could not leave St. Louis without getting permission and she was denied a certain status given to White widows. While attitudes toward race may have been less uniform given the transient nature of the city, African people were still considered inferior to French, English, and Spanish and suffered as a result.

As the city continued to develop, attitudes toward African and African Americans hardened alongside those of the dominant culture and the earlier flexibility felt by some Africans in the city diminished.

Your Turn

How did European views of race impact the cultural and political development of St. Louis? How do they still impact us today?

-

Materials from the State Historical Society of Missouri on Black history in the state.

Guide to St. Louis historical sites, including the Clamorgan’s Alley where the first person of African descendent settled in St. Louis.

-

Article written by K-12 program manager at the Missouri History Museum in St. Louis: Gilbert, L. (2014). “Finding Strength in Stories of the Enslaved,” Social Studies and the Young Learner 27 (2), pp. 18-21.

Southern Poverty Law Center, report: Teaching Hard History: American Slavery.

-

General Resources:

Learn more about Laclede’s Landing Riverfront district in St. Louis - a vibrant neighborhood today.

Books & Articles:

Fausz, J. Frederick (2011). Founding St. Louis: First City of the New West. Charleston, SC: The History Press.

Corbett, Katharine T. (1999). In Her Place: A Guide to St. Louis Women's History. St. Louis, MO: Missouri History Museum.

Gitlin, J. Morrissey, R. and Kasto, P. (2021). French St. Louis: Landscape, Contexts, and Legacy (France Overseas: Studies in Empire and Decolonization). University of Nebraska Press.

Kolb Turnbell, F. (2024). Spanish Louisiana: Contest for Borderlands, 1763–1803. LSU Press.

Archives:

The State Historical Society of Missouri: African American Experience Research Guide.

The State Historical Society of Missouri: French and Spanish Archives, 1763-1841.

Museums:

The Gateway Arch Museum: Colonial St. Louis

-

Clamorgan, C. (1999, reprint). The colored aristocracy of St. Louis. University of Missouri Press.

Smith, D.E. (2017). African American lives in St. Louis, 1763-1865: slavery, freedom and the West. McFarland & Co. Press.

Wright Sr., J. (2002). Discovering African American St. Louis: A Guide to Historic Sites, second edition. Missouri Historical Society Press.

-

Clamorgan, C. (1999, reprint). The colored aristocracy of St. Louis. University of Missouri Press.

Corbett, K. T. (1999). In Her Place: A Guide to St. Louis Women's History. St. Louis, MO: Missouri History Museum

Fausz, J. F. (2011). Founding St. Louis: First City of the New West. Charleston, SC: The History Press.

Smith, D. E. (2017). African American lives in St. Louis, 1763-1865: Slavery, freedom and the west. McFarland Press.

Wright Sr., J. (2002). Discovering African American St. Louis: A Guide to Historic Sites, second edition. Missouri Historical Society Press.