1787: The U.S. Constitution and Black and White Founders

Big Idea

The White founders and writers of the Constitution protected and defended the legality of race-based forced bondage even while Black authors continued to highlight the inconsistent application of freedom and “inalienable rights” in the new country.

What’s important to know?

The Constitutional Convention: The issue of the enslavement of Black people dominated the Constitutional Convention.

The Constitution’s Defense of Enslavement: The results of the debates around enslavement, produced a document that while never using the word “slavery,” enshrined its practices into the laws of the United States.

Black Founders: Black men and women wrote and spoke about real freedom and inalienable rights, laying the groundwork for the human and civil rights achieved later in the nineteenth century.

1: The Constitutional Convention

Likeness of Sally Hemings, who was the enslaved concubine of Thomas Jefferson and believed to have accompanied and served him during the Constitutional Convention.

Image Source: African American Registry

Describing the Constitutional Convention in 1787, James Madison noted that arguments over the enslavement of Black people fueled conflict between the Northern and Southern delegates.

Madison wrote,

[T]he real difference of interest lay, not between the large & small but between the N[orthem] & Southn. States. The institution of slavery & its consequences formed the line of discrimination... [hence]the most material [of differentiating interests among the states] resulted partly from climate, but principally from the effects of their having or not having slaves. These two causes concurred in forming the great division of interests in the U. States. (Wiecek, 2018, p. 62)

To appease both sides, delegates agreed upon what has become known as “the Three-Fifths Compromise.” While the “compromise” sought to find middle ground, it assumed the legality of slavery and provided tacit support by mandating that three of every five slaves be used in the formula to determine states’ federal taxes and the number of states’ congressmen elected to the U.S. House of Representatives (p. 63; Van Cleave, 2010, p. 120).

“The Founding Fathers were visionaries, but their vision was limited. Slavery blinded them, preventing them from seeing black people as equals.”

Investigate

Want to learn more? Listen to historian James Oliver Horton discuss slavery and the Constitution here. Visit the National Archives to explore the original images of the Constitution.

2: The Constitution’s Defense of Enslavement

U.S. Constitution

Image Source: National Archives

While the three-fifths compromise remains the most well-known example of the tacit acceptance of slavery in the Constitution, the Constitution defended the institution in multiple ways.

U.S. Constitution’s defense of the enslavement of Black persons:

Article 1, Section 2 - Counts slaves as 3/5th of a person;

Article 1, Sections 2 and 9 - Bases tax formulations on the 3/5ths principle to avoid indirectly encouraging emancipation of slaves;

Article 1, Section 9 - Protects the Atlantic slave trade until 1808;

Article 4, Section 2 - Forbids the emancipation of fugitives and requires escaped slaves be returned to their masters;

Article 1, Section 8 - Empowers Congress to call up states’ militias to suppress insurrections, including slave insurrections;

Article 4, Section 4 - Obligates the federal government to protect states against domestic violence, including violence perpetrated by slave insurrections;

Article 5 - Provisions outlined in Article 1, section 9, clauses 1 and 4 were not able to be amended (This protected the earlier provisions related to the timeline for the abolishment of the slave trade as well as the compromises related to slavery and taxation);

Article 1, Sections 9 and 10 - Forbids the federal government and states from taxing exports with the goal of exempting goods made by slaves from export duties (Wiecek, 2018, p. 62).

Historian Linda Kerber (1997) noted, “At its founding moments, the United States simultaneously dedicated itself to freedom and strengthened its system of racialized slavery” (p. 841). The foundational legal document of the United States assumed slavery’s legality, reinforced its racial hierarchy, supported the enslavers when it came to fugitive slaves, and put the full military might behind stopping slave insurrections.

The Constitution was to reflect ideals of liberty and freedom, but in reality, for all non-Whites it represented the crowning achievement of White dominance in the New World and enshrined a racialized system into the DNA of the United States.

Students

Want to learn more? Listen to historian Annette Gordon-Reed discuss how the founding documents of the United States protected the enslavement of Black persons.

From Learning for Justice teaching videos.

3: Black Founders

Lemuel Haynes. Haynes fought in the early skirmishes of the American Revolution and became the first African American ordained minister in the States.

Image Source: Wikipedia

The traditional narrative of the founding era is dominated by White men and their documents and actions. However, Black men and women remained central to the formation of the nation and its views of freedom. As Nikole Hannah-Jones noted in her introduction to The 1619 Project, “Black Americans have managed, out of the most inhumane circumstances, to make an indelible impact on the United States, serving as its most ardent freedom fighters and forgers of culture” (Hannah-Jones, 2021).

Black authors, poets, and orators continually highlighted the indefensibility of the United State’s position. In pursuing separation from England, Thomas Jefferson had written these stirring prose: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness” (from the Declaration of Independence). Black authors continually noted the incongruity of stating this as a defining belief of the country, while it enslaved a good number of its inhabitants (most of whom had been kidnapped and brought to the country against their will).

Selections from Black Founders

"Engraved portrait of James Armistead Lafayette (c. 1759-1830)". Lafayette served in the Continental Army as a double-agent, informing on Benedict Arnold and the activities of the British leading up to the Battle of Yorktown.

Image Source: Wikipedia

Below, listen to audio recordings of the works of some of the overlooked Black founders (courtesy of the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History:

Lemuel Haynes (1753-1833)

James Armistead Lafayette (1748-1830)

Jupiter Hammon (1711-1800)

William Hamilton (1773-1836)

Richard Allen (1760-1831)

Venture Smith (1729-1805)

Patty Gibson (letter dated 1797)

Nero Brewster (1711-1786)

Jupiter Nicholson and others (petition dated 1797)

Belinda (1712-1795)

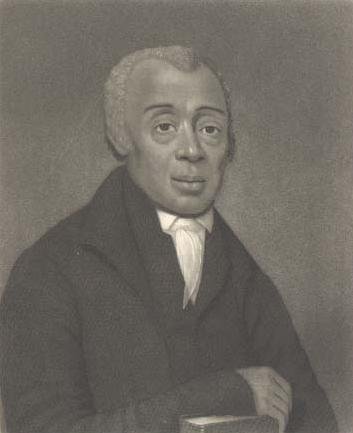

Richard Allen

Image Source: Wikipedia

Spotlight on Richard Allen

Richard Allen represented one of the Black founding fathers. Born into enslavement, he purchased his freedom and later founded the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the first independent Black Christian denomination in the United States.

In 1799, he along with 70 other Black leaders sent a letter to Congress arguing for the international slave trade to be outlawed and a plan be created for the emancipation of enslaved people in the United States. Importantly, they strongly asserted their rights as citizens of the United States. They also addressed the rights of free Black men and demanded protections so that they would not be falsely arrested under the Fugitive Slave Act. (Newman, 2009; McCullough, 2005).

“Black Americans have managed, out of the most inhumane circumstances, to make an indelible impact on the United States, serving as its most ardent freedom fighters and forgers of culture.”

Your Turn

How did the Black founders push our country toward a “more perfect union” and a more honest expression of freedom?

-

Teaching Hard History: American Slavery podcast Episode 10: Slavery in the Constitution

Explore the Museum of the American Revolution’s virtual exhibit of one the United States’ Black Founding Families.

Read African Founders: How Enslaved People Expanded American Ideals by David Hackett Fischer

Explore Free Black Founders, a virtual exhibit from the Library Company of Philadelphia.

Read: Steven Mintz, “Historical Context: The Constitution and Slavery,” from The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.

-

Teaching Hard History: American Slavery Text-Dependent Questions for Key Concept 3, to accompany Annette Gordon-Reed’s video.

Teaching Hard History: American Slavery podcast Episode 10: Slavery in the Constitution

-

Read about the development of the Missouri state constitutions and how the federal constitution influenced them.

-

Gordon-Reed, A. and Onuf, P. (2016). “Most Blessed of the Patriarchs”: Thomas Jefferson and the Empire of Imagination. Liveright.

Gordon-Reed, A. (2008). The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family. W.W. Norton & Co.

Hannah-Jones, N., Roper, C., Silverman, I., & Silverstein, J. (2021). The 1619 Project: A New Origin Story. Random House Publishing.

Horne, G. (2014). The Counter-Revolution of 1776: Slave Resistance and the Origins of the United States of America. NYU Press.

Nunley, T. (2021). At the Threshold of Liberty: Women, Slavery, and Shifting Identities in Washington, D.C. UNC Press.

-

Hannah-Jones, N., Roper, C., Silverman, I., & Silverstein, J. (2021). The 1619 Project: A New Origin Story. Random House Publishing.

Jeffries, H. K. Preface. (2018). “Teaching Hard History.” Southern Poverty Law Center, p. 5. https://www.splcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/files/tt_hard_history_american_slavery.pdf

Kerber, L. (1997, December). The meanings of citizenship. Journal of American History, 84(3), pp. 833-854

McCullough, A. (2005). Richard Allen. Pennsylvania Center for the Book. Pennsylvania State University. https://pabook.libraries.psu.edu/literary-cultural-heritage-map-pa/bios/allen__richard

Newman, R. (2009). Freedom’s Prophet: Bishop Richard Allen, the AME Church, and the Black Founding Fathers. New York University Press.

Van Cleave, G. W. (2010). A slaveholders' union: slavery, politics, and the constitution in the early American republic. University of Chicago Press.

Wiecek, W. (2018). The sources of anti-slavery constitutionalism in America, 1760-1848. Cornell University Press.