1897: Anti-Black Criminology Bias

Big Idea

African American mathematicians and sociologists refuted White arguments of Black inferiority and tendency to criminal behavior utilizing many of the new methods established by W.E.B. Du Bois in the field of sociology.

What’s important to know?

Race Traits & Tendencies: The publication of a book arguing that Black people were naturally drawn toward criminal behavior hardened biases against Black people and in particular, within the field of criminology.

A Scientific Response: Prolific Black author and founder of Howard University’s sociology department, Kelly Miller, wrote a damning response to Race Traits & Tendencies. He demonstrated how the author had wrongly conflated racial characteristics with environmental factors and further noted the inaccuracies of his mathematical calculations.

1: Race Traits and Tendencies

A book published at the end of the nineteenth century wrongly portrayed Black people as prone to violence and criminal behavior.

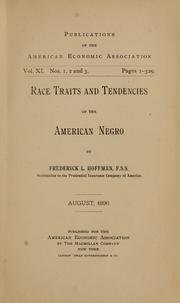

Race Traits and Tendencies of the American Negro

Image Source: Open Library

Around the same time that Plessy v. Ferguson was decided, statistician Frederick Hoffman published Race Traits and Tendencies of the American Negro. In his book, he argued that recent census numbers proved African Americans were headed for extinction. Specifically, he wrote, “[a]ll the facts brought together in this work prove that the colored population is gradually parting with the virtues and the moderate degree of economic efficiency developed under the regimé of slavery” (Hoffman, 1897, p. 328). Not only did he believe that slavery had benefitted the Black community but he further asserted that the cause of their looming extinction was due to “a low standard of sexual morality” (p. 328).

Hoffman used arrest data to argue that higher Black arrest rates indicated African Americans were naturally drawn toward criminal behavior. Rather than understanding the higher arrest rates to be reflections of racist laws, Hoffman blamed Blacks for their incarcerations.

Hoffman’s book influenced and biased the development of criminology in the twentieth and twenty first centuries. Hoffman represented one of many sources that used biased data to influence 20th century criminology against Black people, thereby deepening systemic racism in America, especially within the law enforcement community (Kendi, 2017; Wolf, 2006).

“If democracy cannot control lawlessness, then democracy must be pronounced a failure.”

2: A Scientific Response

Kelly Miller

Image Source: Library of Congress

In 1897, African American mathematician, sociologist, author, and newspaper columnist (not to mention the Dean of Howard University) published a critique of Hoffman’s report. His report was titled, “A Review of Hoffman's Race Traits and Tendencies of the American Negro,” The American Negro Academy. Occasional Papers No. 1.

In his piece, he pointed out how Hoffman’s statistical notations were inaccurate and argued that he wrongly conflated supposed racial traits with environmental factors.

Miller later established the sociology department at Howard University and continued to publish prolifically. He was a respected intellectual and celebrated for his critical acumen and argumentation, as The Boston Transcript described him “No man of his race has so sure a power of prunning [sic] fallacies with passionless intellectual severity” (The Crises, 1914, p. 2).

During World War I, he wrote a letter to President Woodrow Wilson calling out the lack of response to lynching and mob violence in the United States. As part of his argument, he reasserted his argument that race and crime were not connected. He wrote:

In the early stages of these outbreaks [lynching] there was an attempt to fix an evil and lecherous reputation on the Negro race as lying at the base of lynching and lawlessness. Statistics most clearly refute this contention. The great majority of the outbreaks cannot even allege rapeful asssault in extenuation. It is undoubltedly true that there are imburited and lawless members of the Negro race, as there are of the white race, capable of comitte any outrageous and hideous offense. The Negro possess the imperfections of his status. His virtues as well ashis failures are simply human. It is a fatuous philosophy, however, that would resort to cruel and unusual punishment as a deterrent to crime. The Negro should be encouraged in all right directions to develop his best manly and human qualities. Where he deviates from the accepted standard he should be punished by due process of law. But as long as the Negro is held in general despite and suppressed below the level of human privilege, just so long will he produce a disproportionate number of imperfect individuals of evil propensity. To relegate the Negro to a status that encourages the baser insticts of humanity, and then denounce him because he does not stand forth as a model of human perfection, is of the same order of ironical cruelty as show by the barbarous Teutons in Shakespeare, who cut off the hands and hacked out the tongue of the lovely Lavinia, and then upbraided her for not calling for perfumed water to wash her delicate hands. The Negro is neither angelic nor diabolical, but merely human, and should be treated as such (Miller, 1917, 9-10).

Miller continued his efforts to advocate for African American rights arguing that “If democracy cannot control lawlessness, then democracy must be pronounced a failure” (p. 8).

Your Turn

How did the views of race that fueled the enslavement of Africans in the seventeenth century influence nineteenth-century criminology and law? How do these views still influence us today?

-

Read more about Kelly Miller’s life and career.

Read Kelly Miller’s open letter to President Woodrow Wilson.

-

Library of Congress primary source materials for teaching about Kelly Miller.

-

General Resources:

Explore The Race Card Project’s submissions from Saint Louis where residents discuss their views of race in 6 words or less.

The Marshal Project, St. Louis - reporting on criminal justice in St. Louis

Books & Articles:

Graham, David, "Learning From Ferguson: African American Attitudes Towards Community Policing in Saint Louis" (2016). Theses. 282. http://irl.umsl.edu/thesis/282

Gaston, S., & Brunson, R. K. (2020). Reasonable Suspicion in the Eye of the Beholder: Routine Policing in Racially Different Disadvantaged Neighborhoods. Urban Affairs Review (Thousand Oaks, Calif.), 56(1), 188–227. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087418774641

Archives:

The State Historical Society of Missouri: African American Finding Aid

Saint Louis University Museum of Art: Ink Tributes: an Exhibition Highlighting Victims of Police Brutality

-

Du Bois, W.E.B. (1914). The Crises. p. 2. https://transcription.si.edu/view/24945/NMAAHC-2012_84_19_002

Frazier, E. F. (1940). Negro Youth at the Crossroads. American Council on Education.

Hoffman, B. (2003). Scientific Racism, Insurance, and Opposition to the Welfare State: Frederick L. Hoffman’s Transatlantic Journey. The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, 2(2), 150–190. doi:10.1017/S1537781400002450

Banks, W. M. (1996) Black Intellectuals: Race and Responsibility in American Life. W.W. Norton & Company.

-

Du Bois, W.E.B. (1914). The Crises. p. 2. https://transcription.si.edu/view/24945/NMAAHC-2012_84_19_002

Hoffman, F. (1896). Race traits and tendencies of the American Negro. Published for the American Economic Association by Macmillan. https://archive.org/details/racetraitstenden00hoff/page/328

Kendi, I. (2017). Stamped from the beginning: The definitive history of racist ideas in America. Nation Books.

Miller, K. 1863-1939, (1917) The disgrace of democracy : open letter to President Woodrow Wilson. Retrieved from the Digital Public Library of America, http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/005999433

Wolff, M. (2006). The myth of the actuary: Life insurance and Frederick L. Hoffman’s ‘race traits and of the American Negro. Public Health Reports (1974-), 121(1), 84-91. http://www.jstor.org.proxy-ln.researchport.umd.edu/stable/20056918