1820: Missouri Enters the Union as a Slave State

Big Idea

When Missouri joined the Union in 1820, it entered the Union as a “slave state,” effectively enshrining the dehumanizing forced labor practices into the state’s legal system.

What’s important to know?

Missouri’s History of Dehumanization: The Native Americans who had lived on the land now known as Missouri were the first people to receive the dehumanizing treatment that African peoples later experienced at the hands of White colonizers.

The Missouri Compromise: Congress would only allow Missouri to enter the Union if they came in as a “slave” state. While it had previously been a free state, the White leaders of the state agreed to the change further spreading and entrenching forced labor across the United States.

1: Missouri’s History of Dehumanization

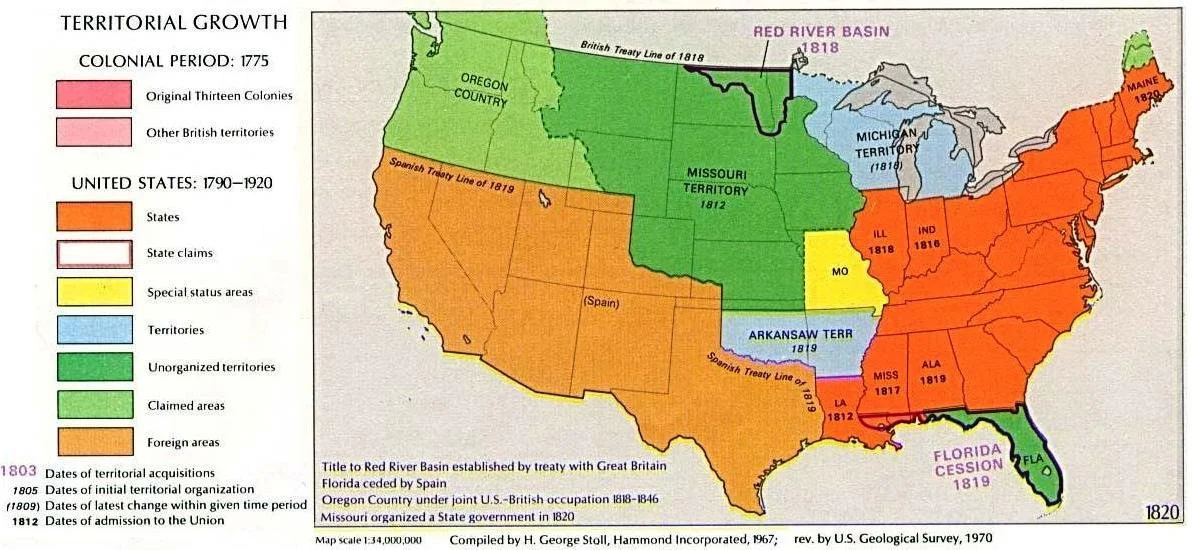

The United States in 1819

Image Source: Wikipedia

Before Missouri formed as a state and joined the United States in 1820, the land had been occupied for over a thousand years by Native Americans including the Osages, Missouris, Iowas, and Omahas. For many of these Native Americans, their treatment mirrored the dehumanizing conditions forced upon Africans in the region. (Native American Genealogy)

2: The Missouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise of 1820 changed Missouri from a free state to a slave state as it entered the Union. As part of the Missouri Compromise of 1820, Missouri entered the United States as a slave state, while the state of Maine entered the United States as a free state to maintain the balance of states allowing slavery and those that did not. The Missouri Compromise also ensured that slavery was illegal above the 36º 30' in the rest of the Louisiana Territory (“Milestone Documents,” 2022, par. 1).

Your Turn

What is the significance of Missouri entering the Union as a “slave state”? How does that legacy still impact the state today?

-

National Park Service resource on St. Louis and the Missouri Compromise.

Documents related to the Missouri Compromise of 1820 from the National Archives.

Materials from the Library of Congress related to the Missouri Compromise.

Digital Maps related to the Missouri Compromise.

Founding Father addresses the Missouri Compromise of 1820, from the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.

Digital resources related to the antebellum era.

-

Teaching materials from the National Archives related to the Missouri Compromise of 1820.

-

General Resources:

Our Missouri Podcast, Episode 34: Commonwealth of Compromise – Amy Laurel Fluker (Border Wars, Part 1)

Books & Articles:

Forbes, R. P. (2009). The Missouri Compromise and Its Aftermath. University of North Carolina Press.

Archives:

Explore the debate for Missouri Statehood as expressed through Missouri newspapers (University of Missouri, Saint Louis).

Museums & Parks:

-

Grayson, S. M. (1996). Black Women in Antebellum America: Active Agents in the Fight for Freedom. William Monroe Trotter Institute Publications. 13.

https://scholarworks.umb.edu/trotter_pubs/13Miles, T. (2024). Night Flyer: Harriet Tubman and the Faith Dreams of a Free People. Penguin Random House.

-

Milestone Documents from the National Archives: https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/missouri-compromise

Native American Genealogy from Jefferson College.