1856: The Preaching of Sojourner Truth and the Caning of Charles Sumner

Big Idea

Conflict over the morality of slavery led to outbreaks of violence in the U.S. capitol. Abolitionists, such as Sojourner Truth, continued to highlight the disparities between White rhetoric around freedom and the legal statutes denying this freedom to Black Americans, and especially to Black women.

What’s important to know?

Vehement Opposition: Senator Charles Sumner vehemently opposed actions in the U.S. Congress to force Kansas to enter the union as a “slave” state, decide Kansas’ request to enter as a free state. His two-day speech, signified the depth of resolve on the part of Black allies to fight enslavement and in so doing, to fight for the protection of democracy in the United States.

A Vision of Freedom: Black anti-slavery advocates continually called the leaders of the Nation to a more consistent and honest application of the principles stated in the founding documents — thereby becoming the truest advocates for and protectors of American democracy.

1: Vehement Opposition

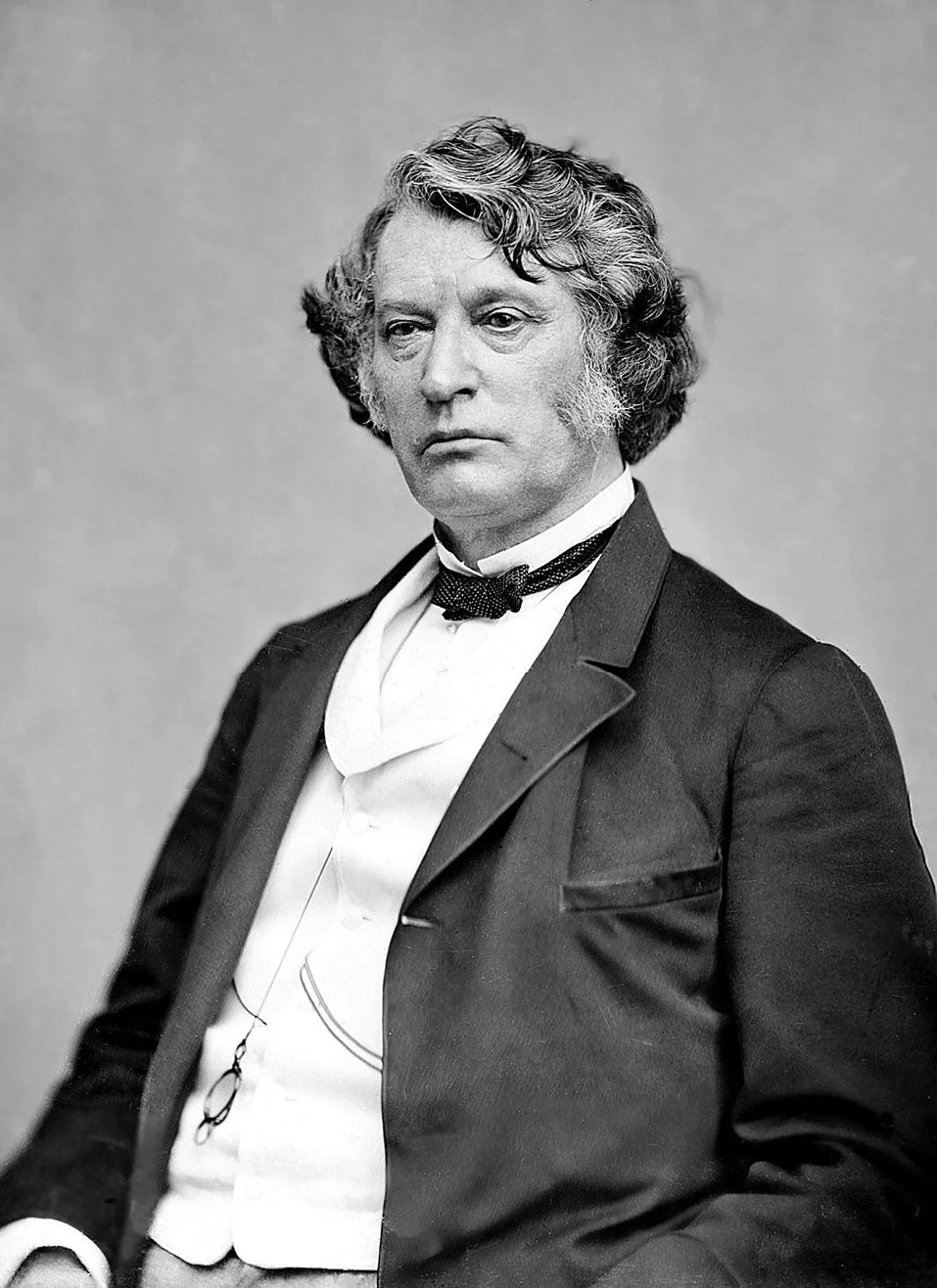

Senator Charles Sumner

Image Source: Library of Congress's Prints and Photographs division

The conflict over slavery reached its zenith during a Senate debate in May 1856. The people in the territory of Kansas had held a Constitutional convention, created a state constitution, voted for that constitution, and then applied for acceptance into the United States as a newly formed free state. Pro-slavery Senators pushed back against this admission because it would have given two more Senate seats to anti-slavery advocates.

Senator Charles Sumner vehemently opposed the attempts by the Southern Senators to block Kansas’ entry. He felt to go against Kansas’ request to enter as a free state would be to undermine the validity of the constitutional process and the voting box - since that is the process they used to come to the conclusion that they wished to enter the Union as a free state.

He gave a speech, “Crime Against Kansas,” that lasted two days and when printed came to a total of 106 pages. His speech exemplified how the debate over slavery pushed leaders of the United States to clarify and define what they meant when they claimed to be representatives of a democratic republic.

“Sir, speaking in an age of light and in a land of constitutional liberty, where the safegaurds of elections are justly placed among the highest triumphs of civilization, I fearlessly assert that the wrongs of much abused Sicily, thus memorable in history, were small by the side of the wrongs of Kansas, where the very shrines of popular institutions, more sacred than any heathen altar, have been desecrated; where the ballot-box, more precious than any work in ivory or marble, from the cunning hand of art, has been plundered; and where the cry ‘I am an American citizen’ has been interposed in vain against outrage of every kind, even upon life itself…

It is the rape of a virgin Territory, compelling it to the hateful embrace of Slavery; and it may be clearly traced to a depraved longing for a new slave State, the hideous offspring of such a crime in the hope of adding to the power of Slavery in the National Government.” (Sumner, 1856, 5).

A staunch anti-slavery advocate, Sumner’s rhetoric represented the tensions existing in Congress as Northern statesmen became more convinced of the immorality of slavery.

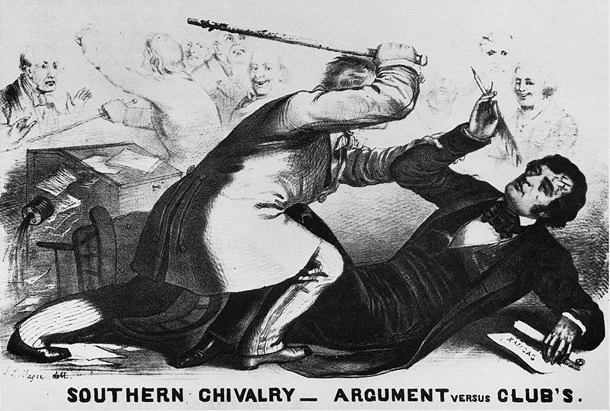

The Caning of Charles Sumner, 1856

Image Source: United States Senate.

Three days later, a representative related to one of the senators Sumner had verbally called out in his speech came into the Senate chamber and beat Sumner ruthlessly. As a Southern statesmen, he felt that the ideas shared by Sumner and other Northerners threatened Southern manhood and economic livelihood. What has become known as the “Caning of Charles Sumner” stands as a vivid demonstration of the dramatic crises the country was facing over slavery’s role in America’s political and economic systems. (Senate.gov, and Sinha, 2003, p. 235-236)

The caning brought into clear focus the shifting views of masculinity and democracy as a result of the ongoing debates around the enslavement of African Americans. Northern representatives became increasingly uncomfortable with what they perceived to be “barbaric” attacks on “the very fabric of American democracy” as represented in the caning of the senator (Sinha, 2003, p. 235). Southerners were aghast that men such as Sumner were arguing that ideal of democracy were applicable to African Americans (p. 235).

2: A Vision of Freedom

Smartly pointing out the inconsistencies that had been in existence since the nation’s founding, Black and White abolitionists rooted their arguments in the vision of a democratic and free nation applying to all its inhabitants.

Throughout these growing tensions, “African-American abolitionists sought to redefine the public discourse on democracy in antebellum America by arguing that racial discrimination and slavery were contrary to American notions of natural rights and representative democracy” (Sinha, p. 236).

Spotlight on Sojourner Truth

Sojourner Truth was a formerly enslaved woman who became an outspoken advocate for abolition and women’s rights. She ran away from her White slave owner in New York and sued him for her son—a case she won.

Sojourner Truth, 1870

Image Source: Wikipedia

Truth stands as a towering figure in American history. Her character, public speaking, and dedication to reform made her stand out even among her noteworthy contemporaries: Frederick Douglas and Harriet Tubman. Her biographer Nell Irvin Painter (2009) has said of her, “Truth was first and last an itinerant preacher, stressing both itinerancy and preaching. From the late 1840s through the late 1870s she traveled the American land, denouncing slavery and slavers, advocating freedom, women’s rights, woman suffrage and temperance” (p. 7).

One of her most well-known sermons/ speeches occurred in Akron, Ohio at a Women’s Convention in 1851. Later termed the “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech, she argued strongly for women’s rights and Black rights—arguing that women were men’s equals and due the same rights. Her preaching skill mixed with political rhetoric created a stirring presentation that captivated all in the room (Truth, p. ).

Her exact words from that speech were not recorded but an account written by prominent feminist and abolitionists Frances Gage is as follows:

“Well, children, where there is so much racket there must be something out of kilter. I think that ‘twixt the negroes of the South and the women at the North, all talking about rights, the white men will be in a fix pretty soon. But what’s all this here talking about?

That man over there says that women need to be helped into carriages, and lifted over ditches, and to have the best place everywhere. Nobody ever helps me into carriages, or over mud-puddles, or gives me any best place! And ain’t I a woman? Look at me! Look at my arm! I have ploughed and planted, and gathered into barns, and no man could head me! And ain’t I a woman? I could work as much and east as much as a man — when I could get it — and bear the lash as well! And ain’t I a woman? I have borne thirteen children, and seen most all sold off to slavery, and when I cried out with my mother’s grief, none but Jesus heard me! And ain’t I a woman?

Then they talk about this thing in the head; what’s this they call it? (Member of audience whispers, ‘intellect.’) That’s it, honey. What’s that got to do with women’s rights or negroes’ rights? If my cup won’t hold but a pint, and yours holds a quart, wouldn’t you be mean not to let me have my little half measure full?

Then that little man in black there, he says women can’t have as much rights as men, ‘cause Christ wasn’t a woman! Where did your Christ come from? Where did your Christ come from? From God and a woman! Man had nothing to do with Him.

If the first woman God ever made was strong enough to turn the world upside down, all alone, these women together out to be able to turn it back, and get it right side up again! And now they is asking to do it, the men better let them.

Obliged to you for hearing me, and now old Sojourner ain’t got nothing more to say” (Truth, 2020, p. 8-9).

Writing about this era, historian Manisha Sinha (2003) argued that, “[p]ublic discussions of the event reveal how the concepts of freedom, democracy, and citizenship were not static but constantly contested. Commentators, North and South, evoked ideas about race and gender to challenge or police the boundaries of republic citizenship and political participation.” (p. 235). And as Sojourner Truth argued, not only were these rights within the domain of men but they also applied to women.

Students

Want to learn more? Listen to scholar Christy Coleman discuss how slavery’s economic impact led to the Civil War.

Video from Learning for Justice.

Your Turn

How did Black men and women develop our country’s understanding of democracy and its rightful application?

-

U.S. Senate information on the caning.

Information from the U.S. Constitution Center.

Read about Kansas’ role in the Underground Railroad

Read:

Sinha, M. (2003). The Caning of Charles Sumner: Slavery, Race, and Ideology in the Age of the Civil War. Journal of the Early Republic, 23 (2), 233–262. https://doi.org/10.2307/3125037

Tameez, Z. (2024). Charles Sumner: Conscience of a Nation. Henry Holt & Co.

-

Various, “Southern Newspapers Praise the Attack on Charles Sumner,” SHEC: Resources for Teachers, accessed February 2, 2025, https://shec.ashp.cuny.edu/items/show/1548.

-

General Resources:

Read about the unrest in St. Louis leading up to the Civil War.

Books & Articles:

Butler, K. (2023). Slavery, Religion, and Race in Antebellum Missouri: Freedom from Slavery and Freedom from Sin. Lexington Books.

Archives:

The State Historical Society of Missouri: African American Finding Aid

Museums & Parks:

-

Blackett, R. (1983). Building an Antislavery Wall: Black Americans in the Atlantic Abolitionist Movement, 1830-1860. Louisiana State University Press.

Du Bois, W.E.B. (1935). Black Reconstruction in America: An Essay Toward a History of the Part Which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, 1860-1880. New York.

Painter, N. I. (1996). Sojourner Truth: A Life, a Symbol. New York: W.W. Norton.

Quarles, B. F. (1974). Allies for Freedom: Blacks on John Brown. Oxford University Press.

Truth, S. (2020, reprint). Ain't I A Woman?. United Kingdom: Penguin Books Limited.

-

Painter, N. I. (1996). Sojourner Truth: A Life, a Symbol. New York: W.W. Norton.

Senate.gov - “Charles Sumner: A Featured Biography.” https://www.senate.gov/senators/FeaturedBios/Featured_Bio_Sumner.htm

Sinha, Manisha. (2017) The slave’s cause: A history of abolition. Yale University Press.

Sumner, C. (1856). The Crime Against Kansas. The Apologies for the Crime. The True Remedy: Speech of the Honorable Charles Sumner of the Senate of the United States, 19th and 20th of May, 1856. https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/resources/pdf/CrimeAgainstKSSpeech.pdf

Truth, S. (2020, reprint). Ain't I A Woman?. United Kingdom: Penguin Books Limited.