1860-1865: Missouri during and after the Civil War

Big Idea

While Missouri entered the United States as a slave state, it entered the Civil War as a border state, with Unionists and Confederates struggling for power. Black men and women risked their lives to aid the Union and to advance the cause of freedom in the state.

What’s important to know?

St. Louis & the Civil War: As a border state, Missouri occupied an incredibly important role in the Civil War. The city’s location on the banks of the Mississippi also made it important for the transportation of goods.

Fighters for Freedom: Many African Americans risked their lives helping Union soldiers and fighting in the Civil War for the Union. Below is the story of one of them - Archer Alexander who lived in southern Missouri.

Enslaved & Free Volunteers: A large number of Black men volunteered to fight for the Union—their efforts resulted in legal changes allowing Black persons to be part of the Union army.

The Journey toward Abolition: At the start of the Civil War, enslaved persons were liberated for 11 days after Major General Frémont issued an emancipation proclamation that President Lincoln then rescinded. After the end of the Civil War, Missouri changed its constitution, abolishing slavery. It also approved the passage of the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments.

1: St. Louis & the Civil War

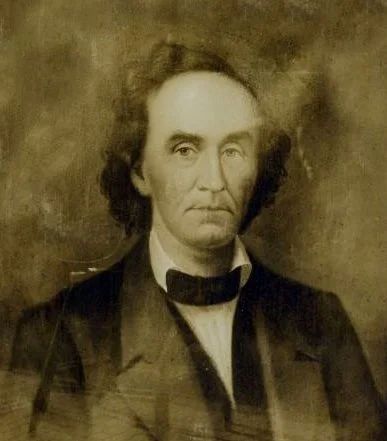

Missouri Governor Claiborne Fox Jackson

After he was elected in 1860 as a “conciliatory” candidate, Fox Jackson immediately began working secretly to support Missouri’s succession from the Union. A task he ultimately failed to accomplish.

Image Source: Wikipedia

Missouri was one of five states considered a “border state” during the Civil War. Border states supported slavery, but did not succeed with the rest of the Southern states. Border states remained critical to the Union as they straddled the geographic regions between North and South. Border states also existed as microcosms of the larger conflicts occurring between states as neighbors divided over allegiance.

As a border state with internal tensions already running high it is not surprising that “one of the first skirmishes following the battle of Fort Sumter occurred in St. Louis in May 1861, when Confederate and Union militia fought over an arsenal in the city” (Campbell, 2013, p. 14). Recognizing the importance of the Mississippi River in supplying war efforts, both sides fought vigorously for control of the state. By August of 1861, martial law had been declared in St. Louis and Confederate property was being seized. Despite significant efforts to the contrary, Missouri remained a border state and thus supportive of the Union throughout the war.

Investigate

Want to learn more? View a letter from 1859 written to enslaved parents from their enslaved son. View the digitized letters and transcriptions at the Missouri State Historical Society here.

2: Fighters for Freedom

Archer Alexander lived in Missouri during the Civil War. His story (reprinted below) represents the risks many enslaved men and women took, especially in border states, to aid the Union and fight for freedom.

Archer Alexander, circa 1870.

Image Source: Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis, Photographs and Prints Collection, N11598

Archer Alexander (ca. 1813-ca. 1880) was born outside of Richmond, Virginia, into a life of slavery. When he was a young boy, his father, Aleck Alexander, was sold away by his master, a man named Mr. Delany. Archer never saw or heard from his father again. When Archer was 18 years old, Delany suddenly passed away, leaving his oldest son, Thomas Delany, in charge of Alexander and his family. When Delany decided to leave home for Missouri, Alexander was chosen to go with him, a decision that separated the young slave from his mother for the rest of their lives. Once in Missouri, Archer met a slave woman named Louisa who lived nearby and "was regularly married to her with religious ceremony, according to slavery usage in well-regulated Christian families" (p. 40). To keep the couple together, Thomas sold Alexander to Louisa’s master. For the next 20 years, Alexander and Louisa lived together in a cabin, raising ten children. In February of 1863, Archer was accused of secretly feeding Union troops information and was ordered to go before an examination committee to be judged. Archer saw mortal danger in reporting to the committee and escaped to St. Louis, obtaining employment working at the home of William Greenleaf Eliot; he continued working for the Eliot family for the remainder of his life. Eliot, the author of the narrative, remained a close and loyal friend to Alexander and his family. After his arrival, Louisa and one of their daughters, Nellie, ran away from their master and joined him in St. Louis. On January 11, 1865, all slaves in Missouri were freed. Louisa died shortly thereafter, and Alexander remarried a twenty-five year-old woman named Judy. Together, the newly married couple moved into their own house, the first Alexander had owned in his life. Judy died in 1879, one year prior to Alexander’s death in St. Louis, Missouri, around 1880. (Excerpt from the digital repository Documenting the American South, The Story of Archer Alexander: From Slavery to Freedom, March 30, 1863, full version found here).

Community Members

Did you know? The current site of Saint Louis University is where one of the first skirmishes of the Civil War occurred. Read more here about some of the more fascinating sites in St. Louis related to the Civil War.

3: Enslaved & Free Volunteers

From the start of the war, free Black men lined up to volunteer for the army. A law from 1792 forbade them from serving and so at first, they were turned away. However, as the war continued and recruits became harder to come by, President Lincoln reconsidered his position.

Battle of Island Mound, March 14, 1863 with African American troops from Missouri

Image Source: Wikipedia

In July 1862, Congress passed the Second Confiscation and Militia Act, which freed slaves who had White owners serving in the Confederate Army. Shortly after, the government began pursuing Black recruits and in 1863 the Bureau of Colored Troops was created to manage the swelling numbers of Black men serving in the Union army. (National Archives)

In June of 1863 the first Missouri Black regiment was formed in St. Louis. Over 300 Black men from the city enlisted. By the wars end, over 8,000 Black Missourians had fought in the Civil War. Not only did the First Regiment soldiers fight for their freedom, following the Civil War they returned to St. Louis and started The Lincoln Institute (later becoming Lincoln University) to provide education to Black Missourians. (Missouri State Archive)

Listen

Listen to this podcast from Seizing Freedom which describes the refugee camps that many Black families lived in during the Civil War.

4: The Journey toward Abolition

At the beginning of the Civil War in August 1861, Union Major-General John Charles Frémont issued an emancipation proclamation in Missouri freeing any enslaved person who was held by a confederate supporter in the state. His proclamation clashed with President Lincoln’s message that the war was about reunification of the states and not about slavery. Fearing Fremont’s proclamation would anger slave holders in the state and tip it toward succeeding, Lincoln rescinded the order 11 days later (Missouri Digital Archive; Sinha, 2013, p. 5).

At the end of the war, on January 11, 1865, elected delegates to the 1865 State Constitutional Convention in St. Louis passed an ordinance abolishing slavery in Missouri. The ordinance to abolish slavery in the state of Missouri passed three weeks before the U.S. Congress proposed the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution abolishing slavery. Missouri was the eight state to ratify the thirteenth amendment, the 17th state to ratify the fourteenth amendment granting citizenship to all Black people, and the 21st to ratify the fifteenth amendment securing the right to vote.

Community Members

Benjamin Gratz Brown

Image Source: Wikipedia

Did you know? Benjamin Gratz Brown (1826-1885) was a lawyer, soldier, and anti-slavery activist in the Missouri legislature from 1852-1859. He opposed the pro-slavery party in the state and helped form the Republican party of Missouri. During the Civil War, he led a regiment and a brigade of the Missouri State Militia. He was a U.S. Senator from 1863-1867 where he voted for Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which abolished slavery. He then served as Governor of Missouri from 1871-1873 (Brown, 2018).

Your Turn

What do you think it was like to live in a border state during the Civil War? How did enslaved Americans help defend and advance the idea of freedom during the war?

-

Materials related to Missouri in the Civil War from the Missouri State Historical Society.

Reference books on the civil war from the National Archives and Records Administration.

U.S. Congressional materialsrelated to the Civil War from the Library of Congress.

Read about Abraham Lincoln and the Border States in the Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association.

U.S. Army historyof African American regiments that fought during the Civil War.

Missouri history of Black regiments and Lincoln University.

History of Lincoln University.

-

Lesson plan about women during the civil war from the Gilder Lehrman Institute for American History.

Teaching the Civil War with primary sources from the National Archives.

Teaching the Civil War with primary sources from the National Archives.

Lincoln and Civil Liberties, a lesson from the Gilder Lehrman Institute for American History.

-

General Resources:

Read about Saint Louis’ engagement in the Civil War.

Read about some of the enslaved men who fought for the Union in Missouri.

Read about Missouri as a border state in the Arizona State University digital archive.

Books & Articles:

Butler, K. (2023). Slavery, Religion, and Race in Antebellum Missouri: Freedom from Slavery and Freedom from Sin. Lexington Books.

Archives:

The State Historical Society of Missouri: Civil War Records.

Museums & Parks:

Wilson’s Creek National Park - site of the first major battle of the Civil War west of the Mississippi

Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site.

-

Glymph, T. (2020). The Women’s Fight: The Civil War’s Battle for Home, Freedom, and Nation. University of North Carolina Press.

Hunter, T. (2017). Bound in Wedlock: Slave and Free Black Marriages in the Nineteenth Century. Belknap Press.

Miles, T. (2015). Tales from the Haunted South: Dark Tourism and Memories of Slavery from the Civil War Era. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN9781469626345

Pinheiro Jr., H. (2022). The Families’ Civil War: Black Soldiers and the Fight for Racial Justice. University of Georgia Press.

Seraile, W. (2003). Bruce Grit: The Black Nationalist Writings of John Edward Bruce. University of Tennessee Press.

——-. (2003). New York's Black Regiments During the Civil War. Routledge.

-

Alexander, A. (1863). The Story of Archer Alexander: From Slavery to Freedom, March 30, 1863. University of Virginia. Documenting the American South.

Brown, Benjamin Gratz. (2018). In P. Lagasse & Columbia University, The Columbia Encyclopedia (8th ed.). Columbia University Press. https://search.credoreference.com/articles/Qm9va0FydGljbGU6NjAzODc5?aid=107448

Brown, B. G. Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

Missouri State Archives: “History of United States Colored Troops” and Timeline of Missouri's African American History.

National Archives: “Black Soldiers in the U.S. Military During the Civil War.” https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/blacks-civil-war

Sinha, M. (2013). Architects of Their Own Liberation: African Americans, Emancipation, and the Civil War. OAH Magazine of History, Vol. 27, No. 2, pp. 5-10.