History

What is this resource and what is its purpose?

The History articles within of The Saint Louis Story provides short summaries - based on scholarship - of key moments in U.S. and St. Louis history that illustrate how ideas around race have influenced the social, political, legal, and cultural development of our nation from its inception. We contend, as do many prominent historians, that belief in Black racial “inferiority” and White racial “supremacy” have shaped our nation as these concepts developed alongside understanding of freedom and democracy.

Each history article is a snapshot. These snapshots are not intended to be comprehensive. Instead, we intend to offer viewers an opportunity to engage with questions and historical insights they may not have previously been exposed to or considered. We provide an overview and build an argument that we hope become the jumping off point for deeper study. Where possible we have referenced and used Black scholars to highlight their important work in the telling of our nation’s history.

Who is our audience?

Students, St. Louis community members, and the general public will find all of the resources on The Saint Louis Story interesting and valuable. In the History section, we have included headings below for students and community members that highlight material geared for or created by these users. At the bottom of each history vignette we also provide additional resources for our diverse audiences.

Students

This header highlights materials geared for middle and high school as well as college students. Community members may also find these resources valuable.

Community Members

This header highlights materials geared for or created by community members. Middle and high school students as well as college students may also find these resources valuable.

1897: W. E. B. Du Bois

In 1897, a rising African American leader William Edward Burghardt Du Bois accepted a position at the historically black college, Atlanta University. Two years later he published one of his seminal works, The Philadelphia Negro, where he discussed his research and findings after spending two years studying African American communities in Philadelphia. His work challenged prevailing racist views and laid out for the sociological field a more scientifically rigorous method of conducting social research.

1897: Criminology Bias

Statistician Frederick Hoffman published “Race Traits and Tendencies of the American Negro.” He argued that recent census numbers proved African Americans were headed for extinction.

1900: City/ County Segregation

The division of St. Louis into city and county became a tool for segregation in the twentieth century.

1904: World’s Fair

The ultimate goal of the City Beautiful movement was to “encourage inhabitants to become more productive and patriotic” (Campbell, p. 18). While most of the ambitious plans for the City Beautiful were not realized, St. Louis and the state of Missouri did invest millions of dollars clearing land, building temporary structures, and diverting waterways to prepare for the 1904 World’s Fair to celebrate the Louisiana Purchase.

1910: The First Great Migration

By 1910, white control of southern rural America, enforced by Jim Crow laws, made life for African Americans in the South intolerable. Hoping to find more freedom and better economic opportunity elsewhere, many African Americans moved with family and friends to the cities, especially northern cities and cities located in border states.

1914: The First World War

African American men volunteered to serve in the Armed Forces and represented the United States on the battlefields in Europe.

1916: Eugenics

The pseudoscience of eugenics became the platform for White scholars to defend their racists ideas furthering segregation and the ongoing dehumanization of African Americans across the United States. Black scholars continued to refute this pseudo-science and assert the reality that race has and always will be a social construct not a scientific fact.

1917: The East St. Louis Riot

On July 2, 1917 mobs of armed white people attacked Black workers at the Aluminum Ore Company in East St. Louis. White workers were upset that the company had hired Black people in an attempt to break a labor strike. The results were disastrous as white workers burned buildings and shot African Americans.

1919: Segregated Medical Care & The Homer G. Phillips Hospital

The complex ramifications for such a racially informed pseudoscience went far beyond simply justifying prejudices and segregation practices, eugenics and such racism had a concrete and direct negative impact on health outcomes for African Americans in the St. Louis region.

1920: The Harlem Renaissance

On July 2, 1917 mobs of armed white people attacked Black workers at the Aluminum Ore Company in East St. Louis. White workers were upset that the company had hired Black people in an attempt to break a labor strike. The results were disastrous as white workers burned buildings and shot African Americans.

1921: The Tulsa Race Massacre

The use of lynching, killing, and violence to “control” the Black population was on national display in the city of Tulsa, Oklahoma when a White Mob attacked innocent Black men, women, and children - killing hundreds and burning down almost an entire section of the city. This attack highlighted the success that Black communities were generating and the ongoing White reaction to Black economic prosperity.

1929: The Great Depression

The American economy crumbled in 1929 with the financial crash, which began a period known as The Great Depression. As with all economic downturns, those closest to subsistence living suffer the most, leaving African Americans disproportionately affected.

1933: The New Deal

African Americans suffered disproportionately under the Great Depression. The programs created to ameliorate some of the effects of the economic crash benefited poor whites and blocked poor Black people.

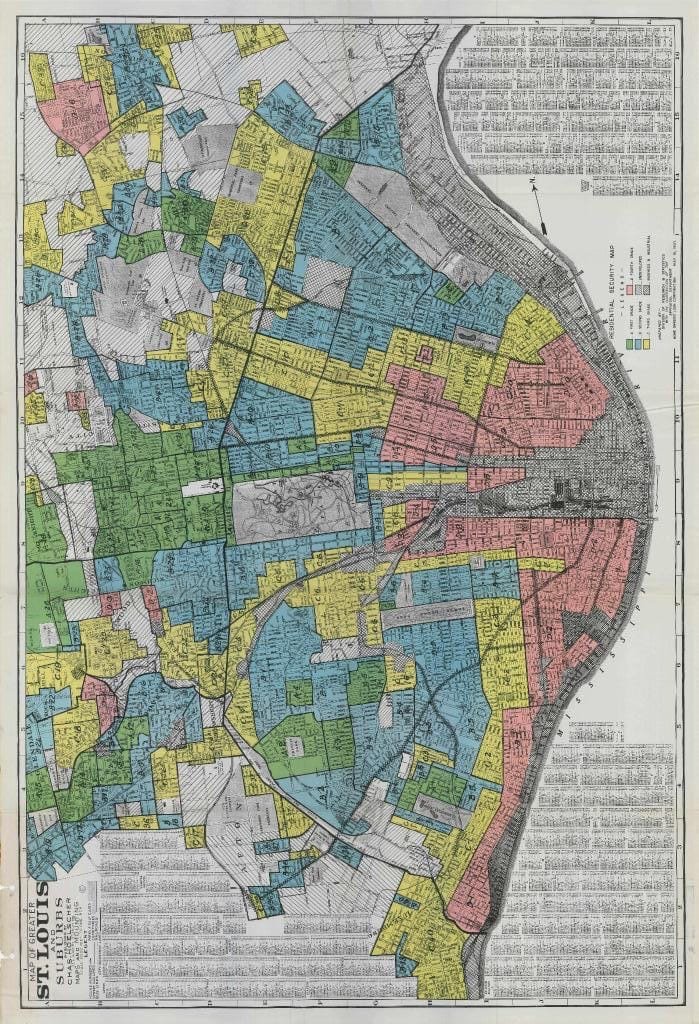

1935: Redlining

The systemic racism underpinning these HOLC maps devastated African American homeownership and generational wealth (wealth and security passed from parents to children) produced by home equity.

1939: Urban Growth, Tuskegee Airmen, and World War II

During the Depression and before WWII, African Americans in Saint Louis continued to struggle.

1940: The Second Great Migration and Literary Giants

During the Depression and before WWII, African Americans in Saint Louis continued to struggle.

1944: The GI Bill and Urban Spaces

One benefit of serving in WWII was the promise of the GI Bill, which provided veterans with assistance through education, job training, and low-cost mortgages; however, African Americans were often excluded from these benefits, because their military service was limited to “mostly menial and low-paying” military roles.

1947: Percy Green and The Gateway Arch

As early as 1935, Saint Louis city leaders and urban developers had discussed a memorial on the Mississippi River. But the roots of the Gateway Arch stretch back to the City Beautiful movement of the early 1900’s when Progressive Era politicians and civic organizers strove to improve the aesthetics of Saint Louis along with its socioeconomic situation. It wasn’t until the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s that the vision of a memorial to America’s past and its future would be designed and built.

1949: “Urban Blight”

“Urban blight” became yet another euphemism that gave white politicians and commercial developers access to areas of the city deemed valuable for future economic development. Despite representing some of the city’s most depressed residents in need of revitalization, African Americans were pushed out, relocated to another depressed area of the city, and left in the same if not worsening circumstances.

1950: Blockbusting

Real estate speculators were increasing their use of a prejudice-driven tactic called “blockbusting'' to clear entire neighborhoods once populated by middle- or upper-class whites and selling or renting houses at large profits to African Americans who had few choices for home ownership. At its most basic level, blockbusting was the process of scaring white people out of neighborhoods so corrupt investors could buy their houses at a reduced price and then sell or rent those same houses to African Americans at a huge profit.