History

Snapshots

In the snapshots below, we aim to show how racial views have shaped our nation's social, political, legal, and cultural development. We argue, as many historians do, that beliefs in Black racial "inferiority" and White racial "supremacy" have influenced our country alongside the goals of freedom and democracy. As we provide these overviews, we have sought to center and reference Black scholars as much as possible. Throughout the entire historuy section, we focus on two themes:

We examine the impact that the United States’ history with slavery and segregation has had on the Black community, particularly by controlling access to where Black people could live (land and housing) and what they could do to make money (economic livelihood).

We explore the ways that the hopes, dreams, patience, frustration, and anger drove the African American community to cultivate thriving communities and to push the United States toward a more perfect expression of our ideals of freedom and democracy.

In conclusion, we hope these snapshots inspire deeper study and promote understanding our history and what has led to many of the injustices we face today so that we are equipped to be better collaborators, problem solvers, and citizens for a more just country and world.

1619: Setting the Course of U.S. History

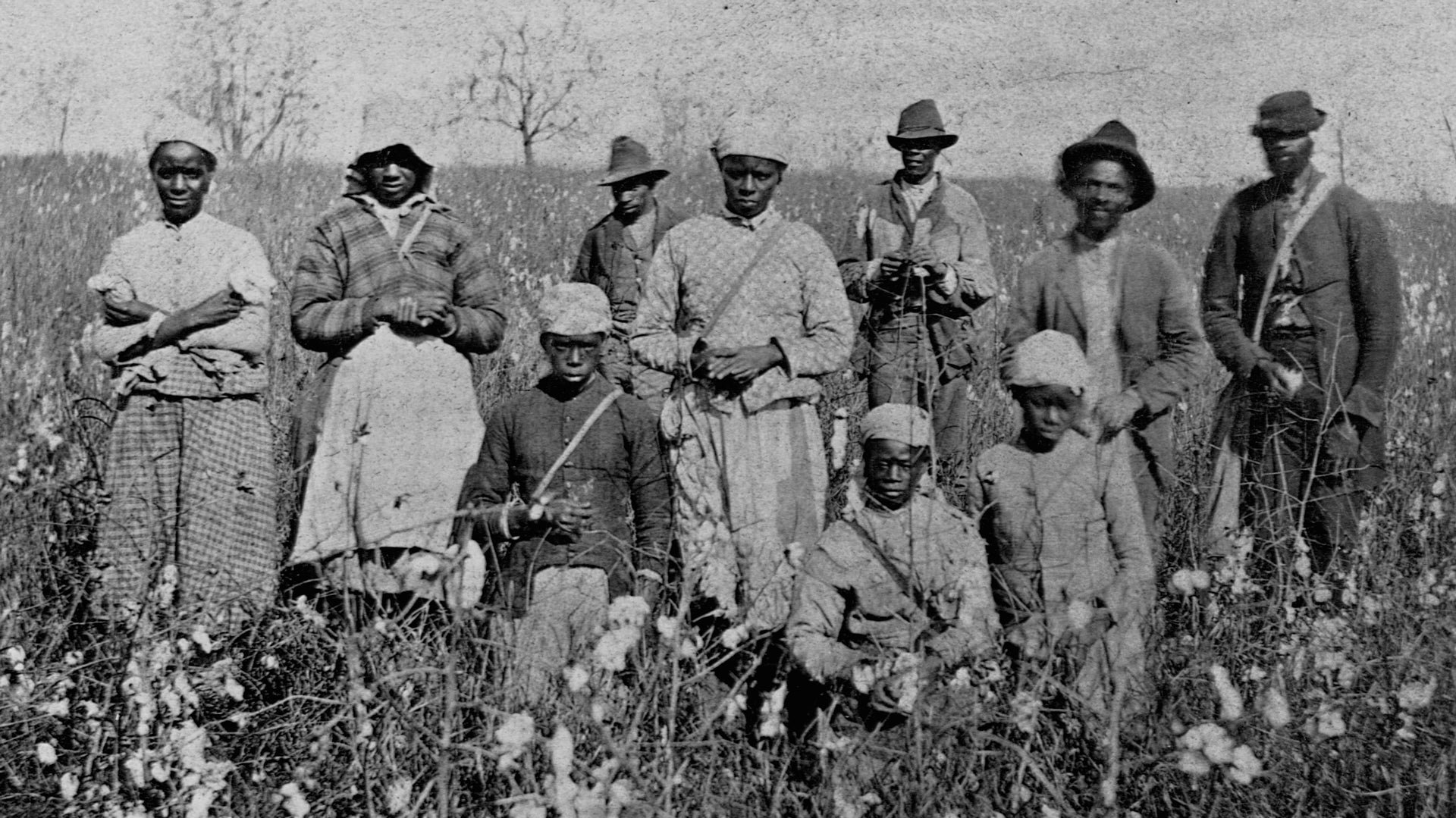

Starting in the early seventeenth century, kidnapping and enslavement brought thousands of African men and women to the shores of America. The enslavement of Africans drove the economic success of the British colonies and what would eventually become the United States of America. Enslaved African men, women, and children asserted their humanity and dignity as they built new lives as enslaved people in North America.

1630: Western Notions of the “Black Race”

The enslavement of African men and women in the American colonies was supported by Western thought and religious interpretation, which portrayed Black people as inferior to White people and cursed by God. As Western views drove justification for enslavement, African men and women resisted dehumanization and asserted their humanity, dignity, and rights.

1662: Black Enslavement Legalized

As White farmers in the colonies became dependent upon African forced labor for economic success, they passed laws that used race as the justification for perpetuating African bondage and forced labor, thereby protecting White cultural, political, and economic dominance.

1718: African Slavery in the French and Spanish Colonies

Free Black men and women in the French and Spanish regions of the Americas maintained their freedom and established independent lives for themselves. Enslaved Africans under French rule were governed by a brutal enslavement code known as the Code Noir—which enforced the racial hierarchy and forced labor of Africans in the Americas.

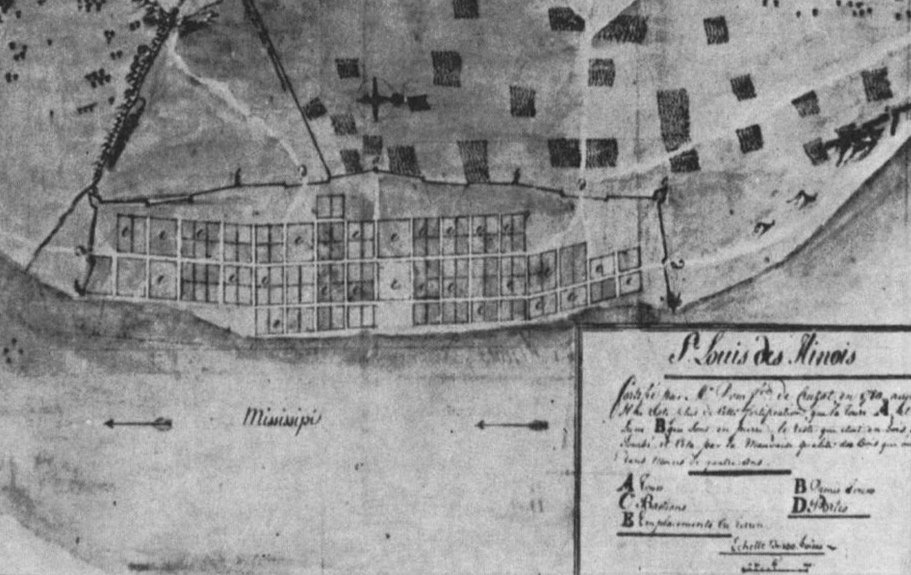

1763: The Establishment of St. Louis and African Arrival

As with other colonial cities, St. Louis’ European population remained influenced by Western notions of race and viewed Africans as inferior to English, French, and Spanish colonists. Despite ongoing prejudice, free Black men and women lived and thrived in St. Louis in the late eighteenth century.

1770-1776: Resistance and Revolution

Fearing loss of control over Black people, American colonists united in their commitment to enslavement and utilized the language of political enslavement as justification for the revolution against Britain. African people across the colonies fought in small and big ways for their liberty and human rights.

1787: The U.S. Constitution and Black and White Founders

The White founders and writers of the Constitution protected and defended the legality of race-based forced bondage even while Black authors continued to highlight the inconsistent application of freedom and “inalienable rights” in the new country.

1790: The Color of Citizenship and Benjamin Banneker

In 1790, Congress passed the Naturalization Act, which denied U.S. citizenship to any Black man or woman, regardless of whether they were enslaved or free. Black Africans continued to assert their rightful citizenship and highlight their role as significant contributors to the development of the United States.

1800: Abolitionism - the Fight for Human Rights

Rebellions against White plantation owners, fleeing enslavement, and forming political and religious movements were some of the many ways Black men and women confronted and resisted the dehumanizing institution of slavery.

1800-1850: Intensifying Debates

Importation of enslaved persons stopped in 1808, but Southern reliance on enslaved labor to fuel it's economy and Northern discomfort with the morality of enslavement created intense political battles in Congress and across the States. Free and enslaved Black men and women continued to assert their claim to the liberties and freedoms enumerated in the founding documents.

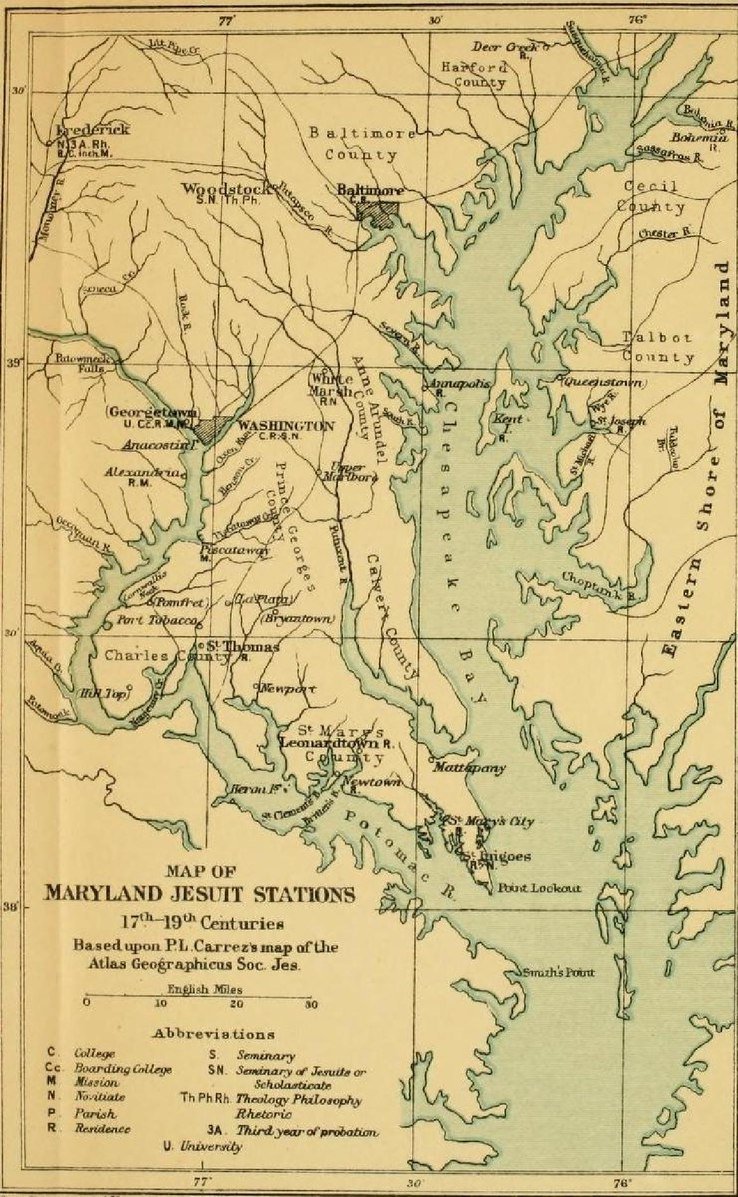

1808: The Catholic Church, the Jesuits, and Enslaved People in St. Louis

The Catholic Church, specifically the Society of Jesus (Jesuits), used enslaved people in St. Louis as forced laborers to build and maintain their farms and schools. Enslaved Black men and women used religion and religious practices as a means of resistance and hope.

1820: Missouri Enters the Union as a Slave State

When Missouri joined the Union in 1820, it entered the Union as a “slave state,” effectively enshrining the dehumanizing forced labor practices into the state’s legal system.

1847: Dred Scott and the Freedom Seekers

Black men and women used the U.S. legal system to fight to be recognized as citizens of the United States and to be provided the same legal protections as White people.

1856: The Preaching of Sojourner Truth and the Caning of Charles Sumner

Conflict over the morality of slavery led to outbreaks of violence in the U.S. capitol. Abolitionists, such as Sojourner Truth, continued to highlight the disparities between White rhetoric around freedom and the legal statutes denying this freedom to Black Americans, and especially to Black women.

1860-1865: Missouri during and after the Civil War

While Missouri entered the United States as a slave state, it entered the Civil War as a border state, with Unionists and Confederates struggling for power. Black men and women risked their lives to aid the Union and to advance the cause of freedom in the state.

1862-1863: Abraham Lincoln, the Emancipation Proclamation, and Colonization

Abraham Lincoln’s efforts during the Civil War were focused on restoring the Union. In 1863, he announced the Emancipation Proclamation as a political tool to weaken the South, even while a year before, he had gathered a group of Black leaders to suggest the best path forward for Black Americans was colonization in another land.

1865-1877: Reconstruction and Rights

After Congress ended slavery, African Americans focused on improving their lives during Reconstruction. The federal government kept troops posted in the South to uphold their rights and ensure the full dismantling of the slave system. Despite progress, violence against Black individuals persisted from those who may have lost the war but did not change their mind about Black inferiority.

1877: Retrenchment and Jim Crow

After Reconstruction, African Americans shifted from resisting enslavement in the institution of slavery to resisting a new racial caste system referred to as “Jim Crow.”

1879: The Exodusters and the St. Louis African American Community

The term Exoduster was given to groups of Black Americans migrating from the South to Kansas during the 1870s. St. Louis was an important stop along their journey and the St. Louis Black community provided significant support to them.

1880: The Advocacy of Ida B. Wells against Lynching

Lynching became an especially horrendous tool used by White mobs as a way to instill fear and enforce racial segregation. Black activists, such as Ida B. Wells, used the press and Black organizations to draw attention to this horrific crime.